本文

<Online Exhibition>The Birth of Hiroshima, Peace Memorial City PART3

CONTENTS

PART3

6. Rebuilding the City

7. Designing Peace

8. The Road to Becoming a City of Peace

9. Present-Day Hiroshima

Before the war, Hiroshima was a castle town. As such, it was characterized by its grid plan and narrow streets, making the large-scale widening of roads one of the biggest parts of the recovery plan for the city reduced to rubble.

Large-scale land readjustment was carried out, reducing privately-owned land in order to have land to use for roads and parks. This project, which went region by region, took approximately 20 years to complete.

The lack of funds was also dire. To gain special support from the national government, the recovery plan for Hiroshima was not simply recovery from the devastation of war, but a new kind of recovery plan enshrined in a special law that held at its core a new philosophy: to build an international peace memorial city. In August 1949, it was the first special law of its kind in Japan to be applied to a specific municipal government, and once approved, the recovery plan was finally put into action.

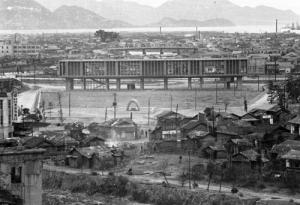

As recovery continued, shanty towns sprang up, illegally occupying the riverbanks. A shanty town in the Moto-machi area, known as the Atomic Bomb Slums, remained until around 1975.

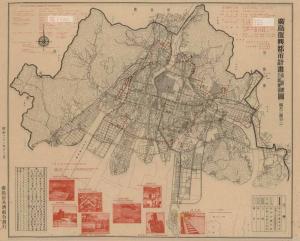

37 Map of the Hiroshima Reconstruction Plan in 1946

December 1946 / Published by Hiroshima-shi-kyosai-kumiai / Collection of the Hiroshima Municipal Archives

38 Restoration of Aioi-bashi Bridge

1946 / Photo by Kishimoto Yoshita

39 The North View from the Center of Hiroshima, near the City Hall, in Autumn 1945

This picture was taken from Chugoku Haiden, present Chugoku Electric Power Co. Inc.

Autumn 1945 / Photo by Kishimoto Yoshita

40 The North View from the Center of Hiroshima, near the City Hall, in November 1947

This picture was taken from Chugoku Haiden, present Chugoku Electric Power Co. Inc.

November 1947 / Photo by Kishimoto Yoshita

41 The North View from the Center of Hiroshima, near the City Hall, in April 1950

This picture was taken from Chugoku Haiden, present Chugoku Electric Power Co. Inc.

April 1950 / Photo by Kishimoto Yoshita

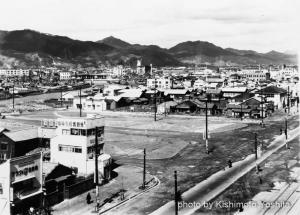

42 The North View from the Center of Hiroshima, near the City Hall, in February 1953

This picture was taken from Chugoku Electric Power Co. Inc.

February 1953 / Photo by Kishimoto Yoshita

43・44 The Visit of Emperor Hirohito to Hiroshima

On December 7th 1947, Emperor Hirohito made a visit to Hiroshima, which drew a large crowd of people who had gathered to catch a glimpse of him.

43 Residents Welcomed the Car Emperor Hirohito Rode at the Entrance of Hiroshima Gokoku-jinja Shrine.

December 7, 1947 / Photo / Collection of the Hiroshima Municipal Archives

44 Emperor Hirohito on the Platform and Citizens

December 7, 1947 / Photo / Collection of the Hiroshima Municipal Archives

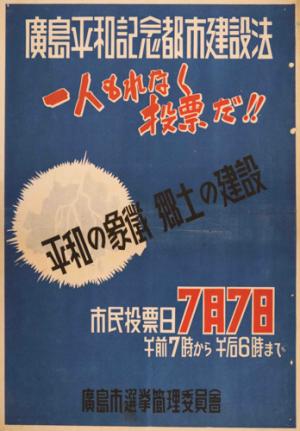

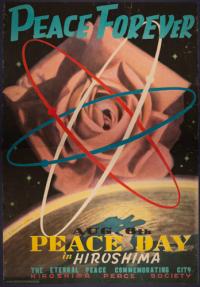

45 A Poster Calling Citizens to Vote for the Hiroshima Peace Memorial City Construction Law

Following the total destruction of Hiroshima, the reconstruction of the city required the use of a former military base owned by the nation. The Peace Memorial City Construction Law was utilized as the legal approach to petition the government for special measures. In May 1949, the bill was unanimously passed by the Parliament.

This law was designed to rebuild Hiroshima as a "peace commemoration city" and to symbolize world peace.

1949 / Poster / Collection of the Hiroshima Municipal Archives

46 “Peace Apartments” by Kyobashi-gawa River

“Peace Apartments” was the first municipal housing with reinforced concrete structure after the war. This apartment block was built on a riverbank 1.7 km from the hypocenter and was named "Peace Apartments".

1951 / Photo by the Public Relations Division, City of Hiroshima / Collection of the Hiroshima Municipal Archives

47 The Reclaiming Work of Hirataya-gawa River

Hirataya-gawa river was an artificial river laid out for the moat of Hiroshima Castle and for a water way in Edo period. Since Meiji era, this river hadn’t used. After the war, this river was reclaimed to road, present Namiki-dori Ave.

May 8, 1952 / Photo / Collection of City of Hiroshima

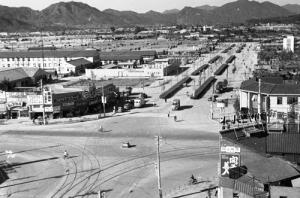

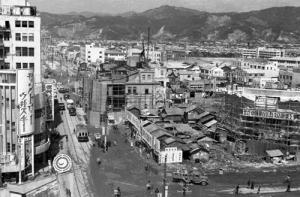

48 The MacArthur Street (Kamiya-cho Intersection)

“The MacArthur Street” was 40 meters wide road that passed through former military base, running between the Prefecture Office and an area that now houses the Hiroshima Rega Hotel. It was named after General Douglas MacArthur as a sign of respect to the GHQ (General Headquarters of the Allied Powers) during the occupation period.

September 30, 1952 / Photo by the Public Relations Division, City of Hiroshima / Collection of the Hiroshima Municipal Archives

49 Kamiya-cho Intersection June, 1958

West side of the intersection, Hiroshima Bus Center was built in 1957. Northern end of Rijo-dori Ave, there was Hiroshima Castle Tower restored in 1958.

June 24, 1958 / Photo by the Public Relations Division, City of Hiroshima / Collection of the Hiroshima Municipal Archives

50 A Road-widening Operation in Hiroshima's Downtown “Hatchobori”

This picture shows road-widening in downtown Hiroshima. Obstacles were removed, and streetcar rails were moved to the center, but paving couldn't keep up due to lack of funds. This caused muddy roads in the downtown area for years, inconveniencing pedestrians.

July 21, 1953 / Photo by the Public Relations Division, City of Hiroshima / Collection of the Hiroshima Municipal Archives

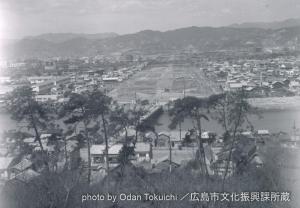

51 The View of 100-meter Road from Mt. Hijiyama

This boulevard was built to transverse the city center and form the south boundary of Peace Memorial Park. The automobile lanes in the center are graced on both sides by walkway lined with trees. It was named “Peace Boulevard (Heiwa Odori) ”, through a public naming contest in November 1951.

April 1955 / Photo by Odan Tokuichi / Collection of Cultural Promotion Division, City of Hiroshima

52 Planting Trees on Peace Boulevard

The Peace Boulevard had been planned and the land secured at an early stage, but for a long time it remained only an open space due to a lack of funds. In 1957, a "tree provision campaign" was started, which called on all local authorities in the prefecture to provide trees. During the two years that the campaign lasted, trees were provided in sufficient quantities to enable the greening of both the Peace Boulevard and the Peace Memorial Park.

November 27, 1957 / Photo by the Public Relations Division, City of Hiroshima / Collection of the Hiroshima Municipal Archives

53 Hiroshima Municipal Baseball Stadium in 1957

A baseball stadium with lighting was built in 1957 by business community donations.

Professional baseball revived after the war, and 1950 saw the birth of the "Carp" local team, which however faced financial difficulties and used a sake barrel at the entrance for donations. Boys contributed money for gloves, and the story became a part of Hiroshima's reconstruction history.

July 22, 1957 / Photo / Collection of the Hiroshima Municipal Archives

54 Hiroshima Municipal Baseball Stadium and the A-bomb Dome (Genbaku Dome )

Around July 1957 / Photo by MIZMAKOBO Co., Ltd. / Collection of MIZMAKOBO Co., Ltd.

55 The Hiroshima Restoration Exposition

The Restoration Exposition was held in April 1958, when the population and industrial production of Hiroshima finally surpassed prewar levels. The exhibits and events of the Exposition were held in the Peace Memorial Museum and other facilities. The numerous visitors to the Exposition could sense that Hiroshima was making a successful recovery.

1958 / Photo by Omae Seiji / Collection of the Hiroshima Municipal Archives

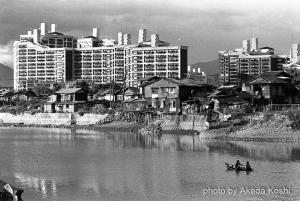

56 Completed High-rise Apartment Buildings in the Moto-machi District and Permitless Shackes on the Honkawa River riverbank

As the riverbanks were gradually transformed into green areas, the illegal buildings after the atomic bombing along the riverbanks progressively disappeared. However, a particular area in downtown Moto-machi known as the "atomic bomb slum" remained until the 1970s, when high-rise apartments were constructed at the rear to relocate the illegal housing residents. In this way, Hiroshima's recovery from the devastation of war was finally completed.

Early 1970s / Photo by Akeda Koshi

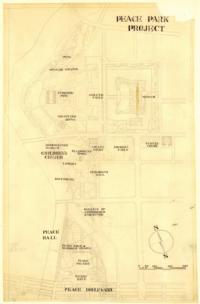

The Nakajima District, once the shopping and entertainment district of the city, was redeveloped as Peace Memorial Park. In April 1949, a competition was held to choose the design for the park and the design created by Tokyo University’s Tange Kenzō and his team won first prize.

His team’s design included placing facilities in a line so that the Atomic Bomb Dome could be seen through an arch-shaped tower that served as a memorial, which could be seen through the pillars of the Peace Memorial Museum when standing facing Peace Boulevard, a 100-meter-wide stretch of road. The arch-shaped tower went on to become the current cenotaph with a haniwa pottery-styled roof, and the design which places the Peace Memorial Museum, Cenotaph for the A-Bomb Victims, and Atomic Bomb Dome on the same axis line is also called the Tange Line.

The balustrades of Heiwa Ōhashi Bridge that spans the Motoyasu River at the entrance to Peace Memorial Park, and Nishi Heiwa Ōhashi Bridge that spans Honkawa River, were both designed by Japanese-American sculptor Isamu Noguchi and have become a symbol of Peace Boulevard. This boulevard makes up the East-West Axis of Peace, and the Tange Line, based on the ideas of Tange and his team, make up the North-South Axis of Peace. Developing the city of Hiroshima around these two Axes of Peace allows the city to inherit the ideology of peace.

57 Model for the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park by Tange Kenzo

1950 / Photo / Collection of the Hiroshima Municipal Archives

58 Peace Park Project

Overall plan for Peace Memorial Park and Chirdren's Center designed by Tange Kenzo Group.

May 25, 1950 / Designed by Tange Kenzo / Plan / Collection of the Hiroshima Municipal Archives

59 The Cenotaph for the A-bomb Victims and A-bomb Doom

The cenotaph was completed in August 1952. In the stone coffin, the Register of the A-bomb Victims are dedicated.

September 16, 1952 / Photo by the Public Relations Division, City of Hiroshima / Collection of the Hiroshima Municipal Archives

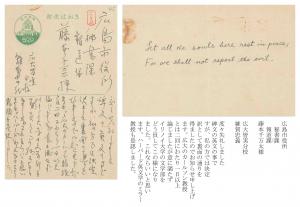

60 The Epitaph of the Cenotaph for the A-bomb Victims

The characters carved in stone on the coffin mean, “Let all the souls here rest in peace, for we shall not repeat the evil”.

August 21, 1952 / Photo by the Public Relations Division, City of Hiroshima / Collection of the Hiroshima Municipal Archives

61 Post Card, Told the English Translation of the Epitaph

The epitaph of the cenotaph for the A-bomb Victims was considered by Saika Tadayoshi, a professor of Hiroshima University. This post card was sent from prof. Saika to a staff of Hiroshima City Hall.

Around 1952 / Post Card / Collection of the Hiroshima Municipal Archives

62 The Baseball Players of the Brooklyn Dodgers Lay Flowers on the Monument

November, 1956 / Photo / Collection of the Hiroshima Municipal Archives

63 Heiwa-ohasi Bridge in 1952

The balustrade of Heiwa-ohashi Bridge and Nishi-Heiwa-ohashi Bridge were designed by Isamu Noguchi, an American sculptor.

October 8, 1952 / Photo by the Public Relations Division, City of Hiroshima / Collection of the Hiroshima Municipal Archives

64 Isamu Noguchi and Tange Kenzo inspect Nishi-Heiwa-ohashi Bridge construction site.

The right end of man is Tange Kenzo who designed Peace Memorial Park, and the third from the right is Isamu Noguchi.

November 27, 1951 / Photo by the Public Relations Division, City of Hiroshima / Collection of the Hiroshima Municipal Archives

65 Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park under Construction

August 5, 1953 / Photo by the Public Relations Division, City of Hiroshima / Collection of the Hiroshima Municipal Archives

66 Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum under Construction

December 2, 1954 / Photo by the Public Relations Division, City of Hiroshima / Collection of the Hiroshima Municipal Archives

67 The Whole View of Peace Memorial Park

July 31, 1958 / Photo by the Public Relations Division, City of Hiroshima / Collection of the Hiroshima Municipal Archives

Initiatives by Hiroshima to realize peace began even before the Hiroshima Peace Memorial City Construction Law was established in 1949.

During the first Peace Festival held in August 1947 (which has been held every year since, except in 1950, under different names), appeals were made not just for the repose of the victims of the atomic bombing, but also for the realization of world peace.

In 1954, the exposure of the Lucky Dragon No. 5 fishing boat to radioactive fallout from a nuclear test carried out at Bikini Atoll spurred a national movement to prohibit atomic and hydrogen bombs. The next year, the very first World Conference Against Atomic and Hydrogen Bombs was held in Hiroshima, making the city a global symbol of the nuclear weapons abolition movement. This World Conference helped to spread awareness of the plight of the hibakusha and the realities of the atomic bombing, and contributed to the beginning of a new movement in offering them relief.

In order to convey the damage from the atomic bombing, a facility displaying tiles, rocks, and other objects that were exposed to heat rays in the bombing opened in 1949 in Moto-machi’s Central Community Hall. This project was inherited by the Peace Memorial Museum, where they continue initiatives to collect atomic-bombed artifacts and testimonies about the bombing, as well as pass on the experience of the atomic bombing.

68 Hamai Shinzo, the Mayor of Hiroshima Presenting His Peace Declaration at the 1st Peace Festival

August 6, 1947 / Photo by Stephen Kelen

69 The Poster for the 3rd Peace Festival

The poster was sent to 161 towns of the world.

1949 / Poster / Collection of the Hiroshima Municipal Archives

70 The Display of A-bomb Materials in ”Atom Bomb Memorial Hall”

August 27, 1952 / Photo by the Public Relations Division, City of Hiroshima / Collection of the Hiroshima Municipal Archives

71 Peace Memorial Ceremony on the 10th Anniversary of the Atomic Bombing

Since this was also the day when the World Conference Against Atomic and Hydrogen Bombs started, many people participated in the Ceremony. It is said that more than 50,000 people visited the Cenotaph. The Peace Memorial Museum finally opened during the latter half of this month. However, there were still barracks set up inside the park.

August 6, 1955 / Photo by Akeda Koshi

72 The 1st World Conference Against Atomic and Hydrogen Bombs, held in Hiroshima

Following the hydrogen bomb testing on Bikini Atoll, the grassroots anti-nuclear movement grew into a nationwide campaign for a petition to ban atomic and hydrogen bombs. 25 million signatures were gathered for this petition. To commemorate the success of the petition as well as the 10th anniversary of the atomic bombing, the World Conference Against Atomic and Hydrogen Bombs was held in Hiroshima. Recognizing the provision of relief for atomic bomb survivors as its major issue, this Conference maintained that "banning atomic and hydrogen bombs is the only true way for survivors of the atomic bombing to find relief".

August 6, 1955 / Photo by Akeda Koshi

73 The A-bomb Dome under the 1st Preservation Construction

Preservation of the dome was controversial, but in 1966, Hiroshima municipal assembly decided to do so “in perpetuity.” The first preservation project was carried out in 1967 after nationwide fundraising campaigns.

July 1967 / Photo / Collection of the Hiroshima Municipal Archives

74 The A-bomb Dome Today

In December 1996, the A-bomb Dome was registered on the UNESCO World Heritage List as a symbol of nuclear abolition and the vow of the human race to pursue peace.

May 23, 2022 / Photo by the Public Relations Division, City of Hiroshima / Collection of the Public Relations Division, City of Hiroshima

75 The Present Peace Memorial Park and Vicinity

October 1, 2022 / Photo by Public Relations Division, City of Hiroshima

76 The View of Peace Memorial Park Area and Central Hiroshima City from West

February 27, 2023/ Photo by Public Relations Division, City of Hiroshima

77 The View of Hiroshima Castle and Central Hiroshima City from Northeast

February 27, 2023/ Photo by Public Relations Division, City of Hiroshima

78 “Toro-nagashi ”

Japan has a summertime custom of floating paper lanterns down rivers and out to sea in order to console the souls of the dead. On August 6 in 1945, many Hiroshima citizens perished in the city's rivers, into which they had gone to seek relief from their burns or to escape the conflagration. Besides consoling the souls of these dead, Hiroshima's lantern festival is also an event that prays for peace.

August 6, 2015 / Photo by the Public Relations Division, City of Hiroshima / Collection of the Hiroshima Municipal Archives

<Online Exhibition> The Birth of Hiroshima, Peace Memorial City

PART3

Contact us if you would like to ask about these images.

Contact Information

Hiroshima Municipal Archives

4-1-1 Ote-machi, Naka-ku, Hiroshima City, Japan 730-0051

FAX:082-542-8831

E-mail:koubun@city.hiroshima.lg.jp